Warrior was a British anthology comic book in the 1980s edited by Dez Skinn and which rivaled 2000 A.D. (the source of Judge Dredd, among other things) in terms of critical acclaim for its stories, but never had the same sales as the other magazine. The contributors to the title were a who’s who of British creators in the 1980s: John Bolton, Steve Dillon, Garry Leach, Steve Moore, Grant Morrison, Paul Neary, Steve Parkhouse, John Ridgway, and many others—notably Alan Moore, who ran The Bojeffries Saga, Marvelman, Warpsmith, and V for Vendetta in the magazine.

At least until it was cancelled.

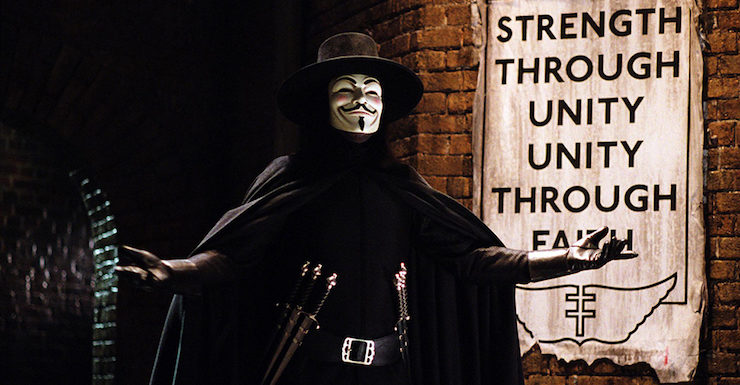

A dystopian science fiction story, Moore’s tale was at least partly inspired by the reign of Margaret Thatcher as prime minister of the United Kingdom as well as the Cold War paranoia about nuclear war and what the world would look like after the bombs flew. It was artist David Lloyd who came up with the notion of V wearing a Guy Fawkes mask.

Unfortunately, Warrior was cancelled in 1985 before they could finish the storyline. (Ditto Marvelman, as it happens.) There was a great hue and cry for the story to be finished by its fans, and finally DC—flush from the success of Moore’s Watchmen—offered to let them complete it. DC put out a ten-issue miniseries that reprinted the Warrior stories and then had Moore and Lloyd finish it. DC also printed it in color—Warrior was a black-and-white magazine.

While not as big a hit as Watchmen, V for Vendetta was quite popular in the U.S. even as the Berlin Wall was coming down and the Soviet Union collapsed.

Buy the Book

Vengeful

Joel Silver bought the rights to both Watchmen and V for Vendetta in 1988. Like so many comic book properties, it languished in production hell throughout the end of the 20th century and finally got made in the 21st, a running theme in this rewatch. In the case of V, it was the Wachowskis’ love for the source material combined with their ability to more or less write their own ticket after the success of the Matrix movies that enabled them to work with Silver to put the movie together.

James McTeigue was hired to direct the Wachowskis’ script, and a first-rate cast was assembled, including Natalie Portman as Evey, John Hurt as the high chancellor (an ironic bit of casting, since Hurt played Winston Smith, pretty much the opposite role, in another dystopian adaptation, 1984), Stephen Rea as Finch, and Stephen Fry as Deitrich. Hugo Weaving plays V, taking on the role after James Purefoy quit after a few weeks of filming, as acting in the mask proved more than he was willing to deal with. Some footage of Purefoy was used in the final film—all of Weaving’s dialogue was looped in later in any case.

Moore, having had a falling out with DC, having been utterly disgusted with film adaptations of The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen and From Hell, and having intensely disliked the Wachowskis’ script, disassociated himself completely from the movie. He refused to be credited as the co-creator of the original comic on which it was based (only Lloyd is credited in the film), and refused to accept any money for it.

Since the Wachowskis were writing a screenplay for a movie that would be released in the mid-2000s, it wound up being a more direct critique of the U.S. in the George W. Bush era of post-9/11 insanity, instead of the UK in the Thatcher era of nuclear paranoia. The movie wound up being quite popular critically and financially, though it was also wracked with controversy, as any good (or even bad) political film would be.

“Both victim and villain”

V for Vendetta

Written by the Wachowskis

Directed by James McTeigue

Produced by Joel Silver and Grant Hill and the Wachowskis

Original release date: March 17, 2006

We open with a flashback to Guy Fawkes and the Gunpowder Plot, then we see both Evey Hammond and V getting dressed (the former in a nice black dress, the latter in a Guy Fawkes mask, fedora, and black wig) while watching Lewis Prothero’s government propaganda TV show. Evey goes out after curfew for a dinner date with her boss, Gordon Deitrich, but is stopped by people she thinks are muggers, but who turn out to be law officers (“Fingermen”), who want to have their way with her before arresting her.

However, V arrives and takes care of the officers and saves her life. He invites her to a rooftop to watch the destruction of the Old Bailey, which he has orchestrated (literally, as he’s commandeered the government speakers on the streets to play the 1812 Overture). The government, led by High Chancellor Sutler, covers this up by saying it was a deliberate demolition, but a lot of people don’t buy it.

After watching the event with V, Evey goes back home. The next day, she reports to work and tells Deitrich that she’d seen Fingermen out and didn’t want to risk being caught, which was almost true.

Inspector Finch, who is in charge of investigating crimes, finds footage of the terrorist whom they believe blew up the Old Bailey, and while they can’t identify him, they can identify Evey. They break into her apartment first, but she’s not there, so they head to her office at BTN. V also is at BTN, threatening to blow up the place with explosives attached to his chest, and sends out a message to all stations. He knew the High Chancellor would send a message to everyone on all channels, as it were, so he is able to get out his own message: that he blew up the Old Bailey on the 5th of November, and that he urges everyone to gather at the House of Parliament a year hence.

Finch and his deputy, Dominic, arrive in pursuit of Evey, and try to stop V, but he has put masks, hats, and wigs on everyone in the studio, so no one knows who is who. One of the officers shoots an innocent in the Fawkes mask, and later the government uses that footage as “proof” that the terrorist is quite dead.

V himself is almost caught, but Evey saves him by distracting Dominic with mace. But Evey is knocked unconscious, and so V absconds with her to his lair, which is filled with forbidden art that he liberated from the government’s archive. Evey is a fugitive now—Finch and Dominic were there specifically looking for her—and so she must stay with V.

Prothero is watching his own show while showering, gloating about how, if he’d been at the studio, he’d have shown V a thing or two. V then shows up—calling him “Commander Prothero”—and kills him, proving him very wrong. The government story is that he died of heart failure while working. But Evey watches the news footage and knows the anchor is lying (she blinks more when she lies), and V admits to killing Prothero.

Finch researches Evey, and learns that her brother was killed during a terrorist attack on St. Mary’s—one of three instances of biological terrorism—and that her parents became political agitators. Her father was killed during a riot and her mother was taken away by the “black baggers” run by Peter Creedy.

V conscripts Evey—who always wanted to be an actor—to role play as the prostitute hired by Bishop Lilliman. Evey warns Lilliman that V is going to kill him, but the bishop thinks it’s part of the role play. Then V breaks in and kills him, allowing Evey to run away.

She takes refuge with Deitrich, and finds out that he’s a radical—a homosexual (he invites women who work for him to dinner to keep up appearances) who has a bunch of radical items hidden away (including a Qu’ran). He puts her up while he continues to do his comedy show, but he goes too far when he throws away the censor-approved script and instead makes fun of the high chancellor, having him menaced by V while “Yakety Sax” plays. Sutler, not being much of a Benny Hill fan, orders Creedy to have Deitrich taken away. (He is initially just arrested, but when they find that he has a Qu’ran, he’s put to death.)

Evey is also captured, and put in a cell, her head shaved. She’s tortured for information on V’s whereabouts, but she refuses to give in.

Finch’s investigation leads him to the Larkhill Detention Center, a place that Lilliman and Prothero had in common, but they can find no records of what Larkhill did, exactly, before it burned to the ground in a major fire. However, another employee in the tax records (which is the only thing left intact, as the one thing governments never lose or mess up is tax records) changed her name and is now the coroner. V visits her and kills her as well. We learn that V was imprisoned at Larkhill, and is likely responsible for its destruction.

Evey refuses to give up anything about V. She finds a note written on toilet paper in a hole in the mortar between her cell and the next. It was written by a woman named Valerie, a lesbian and an actor, who was taken away and imprisoned, and eventually killed.

Given one last chance to give V up, Evey calmly says she’d rather die—and then she is freed. It turns out that V did all this in order to get her to stop feeling fear. She’s furious and leaves, though he does extract a promise to see her one more time before the 5th of November.

Acquiring a fake ID, Evey manages to survive under the radar. She bumps into someone she knew in a grocery store, but the friend doesn’t even recognize her with the buzz cut and new attitude. (She also watches The Count of Monte Cristo again, a movie that V showed her and which he says is his favorite.)

As the 5th gets closer, Sutler is getting more furious at the inability of his people to stop V. More and more people believe in what he’s been saying, and it’s worrisome, even with the uptick in arrests and propaganda. And then Fawkes masks, hats, and wigs are mailed to hundreds of people in London.

Finch is worried that someone’s going to do something particularly horrible and everything will explode. Sure enough, a teenage girl defaces a government poster with a V symbol and is shot and killed, which gets the citizenry riled up into a riot.

Another lead materializes when Finch is contacted by Rookwood, another person connected to Larkhill. They meet at the St. Mary’s memorial, and he tells the story of a man who came to power, who worked to frighten the people, who set up experiments in a prison in order to find a nasty biological weapon. But it was his right hand who suggested targeting, not foreign enemies, but their own people and blame it on outside forces. The fear following the three “terrorist” attacks leads to Sutler becoming high chancellor, Creedy by his side.

Rookwood tells Finch that he’ll contact him again about testifying more openly once he knows that Creedy is under surveillance by Finch’s people. Finch does so.

Of course, Rookwood is actually V—even before the script reveals it, that was Hugo Weaving’s voice—and V goes to Creedy with a modest proposal. He believes that Sutler is losing faith in Creedy and now has him under surveillance by Finch. (Ahem.) If Creedy wants V’s help, he should make an X in his door.

Evey comes to visit V as promised. He reveals that the note from Valerie was real—she was in the cell next to him at Larkhill. They dance at his request—”A revolution without dancing is a revolution not worth having!”—and then he shows her the train and tracks he’s spent ten years rebuilding (the Underground was destroyed in one of the faux terrorist attacks) filled with explosives that he will send to Parliament. Or, rather, that Evey will, if she wishes. He puts that metaphorical loaded gun in her hand and walks away to confront his maker.

He meets with Creedy, who had put the X on his door. Even as Sutler’s recorded message to the people that justice will be swift and merciless, Creedy brings Sutler to V, who cries like a baby. Creedy shoots him, and then has his people shoot V. However, he’s wearing armor, and the experiments at Larkhill made him somewhat superhuman, so while he’s badly wounded, he’s still in good enough shape to kill Creedy and his people before they can reload.

Stumbling back to the train, he dies in Evey’s arms. She puts him on the train, and is about to start it when Finch shows up.

Meantime, hundreds of people in Fawkes masks, wigs, and hats are marching on Parliament. Absent orders (Sutler and Creedy both being dead and all), the soldiers guarding Whitehall don’t do anything. Evey convinces Finch that he should let her do what V wanted, and she sends the train off. It destroys Parliament, and everyone takes their mask off to watch.

“Vindicate the vigilant and virtuous”

The biggest negative about this film in my own opinion is that way too many people see Guy Fawkes masks as a symbol of heroism and resisting fascism when, in fact, it’s the symbol of a religious zealot who tried to commit mass murder and install a totalitarian theocracy. We’re supposed to remember the 5th of November because Fawkes failed.

But whatever. The mask actually works nicely because Fawkes is a figure who has two sides, those who praise his goals and those who condemn him, and it fits perfectly with the duality theme that runs through the entire movie. McTeigue plays up the duality angle quite heavily, far more so than the comic book did, to good effect. There’s the parallel kidnappings of both Evey’s mother and Deitrich, with Evey watching in horror under the bed. There’s the parallel cooking of the same egg dish while greeting Evey in French by both V and Deitrich (though Evey commenting on it kinda ruins it). There’s both V and Evey emerging from their torment drowned in an element, V in the fire he created, Evey in the water of a nasty rainstorm. The use of the letter V and the number 5 (the Roman numeral for five is “V,” after all) is a consistent and well-placed motif throughout the film as it was in the comic book.

One of Moore’s complaints about the script was that the words “fascism” and “anarchy” never come up and he accused it of being too much a critique of American conservativism and should have taken place in the U.S. if that was the case. First of all, the only time those words come up in the comic book is in a spectacularly hamfisted sequence that is, frankly, insulting to the reader’s intelligence. The story works better if you don’t beat people’s heads with it. Anyhow, yes, it’s a critique of American conservativism—in fact, the rise of Sutler to power is a bit too eerily prescient of what’s been happening in this country the past couple of years—but it’s also very obviously fascism, and the fact that the word isn’t used doesn’t mean the critique isn’t there.

Anarchy is avoided, yes—V comes across as more of a freedom fighter, though in truth he mostly seems to be after revenge for what was done to him. In fact, it’s not clear what V’s real motive is, in either the comic or the movie, which is kind of the point. He’s a symbol, and the thing about symbols is that they can be interpreted.

The timing of the movie’s release couldn’t have been better. It was right around late 2005—when President George W. Bush so thoroughly botched the federal response to Hurricane Katrina—that the wheels started to come off the Bush presidency and the horrible things the country had gone through since some crazy people flew planes into buildings in 2001 started to come into focus. The war on terror, the use of torture as an interrogation tool, the PATRIOT Act, the TSA—these were appalling restrictions on liberty for a false sense of security, and the public was belatedly starting to push back against them. (They also finally remembered that Bush was not a popular president. His approval rating on the 10th of September 2001 was only slightly higher than anal warts.) The mid-aughts was the perfect time for a critique of Bush-era America, just as the mid-eighties was the perfect time for a critique of Thatcher-era England.

Many of the changes that were made were necessary simply because it isn’t the mid-eighties anymore. Having the dystopia be the result of biological terrorism makes considerably more sense in the early 21st century, as that’s the current fear of how we’re all going to die. The nuclear war that seemed almost inevitable in 1983 is still a fear now, but a less prevalent one. The movie also dispenses with the supercomputer that runs things, as it probably seemed very plausible 35 years ago, but looks absurd now.

Most important, though, is that in the movie, Evey is an actual worthwhile character. The Evey of the comic was a caricature at best, a victim of V’s manipulations. Her transformation at the end didn’t feel earned because there wasn’t anything there in the first place. The comics’ Evey is so pathetic that it seems V picked her precisely because she was so vapid, so mindless, so useless that he could easily imprint on her and give her the Stockholm Syndrome she needed to be his successor/symbol/protogée.

Natalie Portman’s Evey, though, actually has some agency. She feels like a worthy person for V to take under his cape, as it were. V’s “freeing” her via torture still comes across as horrendous, and something that mostly proves that V is no kind of hero.

But then, I’m not sure he’s meant to be. He’s an extreme symbol that’s necessary to shake people out of their complacency. His very acts of rebellion are inspiring to people, from the teenager who defaces a poster (and gets herself shot) to the people who take up arms against her killer to the hundreds of people who storm Parliament at the end in Fawkes masks to Evey pulling a lever to blow up Parliament on his behalf and continuing his work.

My favorite character in both the comic and the movie is Finch, beautifully played in the movie by the great Stephen Rea and his hangdog face. This is my own personal thing, but I loves me a good workaday cop who’s just trying to close the case and figure it all out. Yes, he’s part of the system, but he’s smarter than most, and he’s not a bad person, just someone trying to get through the day and do his job.

His is but one of many superlative performances. Portman can be hit or miss, but she’s stellar here, showing Evey’s growth. Rupert Graves is delightful as Finch’s partner, Tom Pigot-Smith is magnificently slimy as the Dick Cheney/Donald Rumsfeld equivalent, and Stephen Fry is his usual amazing self. (In the comics, Deitrich was just some random dude Evey hooked up with after she left V, and he was a criminal killed by another criminal. The Wachowskis made him an actual character, a closeted homosexual and free thinker, who thinks his position of popularity as the host of a comedy show makes him more immune than it actually does. It’s a change from the comics that is actually far more effective, especially with the always subtle and brilliant Fry in the role.)

Most impressive to me is Weaving, whom I’ve never been a fan of. I hated him in The Matrix, I hated him in The Lord of the Rings, and I expected to hate him here, but he surprised me. The use of body language is superb (though I wonder how much of that is Weaving, how much is Purefoy, and how much is the stunt double), but in particular Weaving manipulates his voice magnificently. It’s an amazing performance, the best one I’ve seen Weaving give, and I wonder if his almost nonexistent capacity for facial expression is the problem in his other roles, one he’s freed from in this role.

Then we have John Hurt. I have to admit, I prefer the Leader Adam Susan in the comics to the movie’s High Chancellor Adam Sutler—the name was changed to make him sound more like Hitler, a level of sledgehammer-ness the movie doesn’t need. Susan is a quieter, more complex character, one who seems to really believe in what he’s doing and in England. Sutler’s is far less subtle and the only reason the character works is because Hurt, one of the greatest actors of our time, sells it.

V for Vendetta remains an important work in either form. (Right here on Tor.com, Emmet Asher-Perrin wrote a particularly heartfelt discussion of the film in the wake of the 2016 Orlando shootings.) I strongly recommend reading the comic, as it tells the story in a much different, but equally effective manner. It’s interesting, some sequences are almost exactly the same (the coroner’s death scene in her bedroom, a quiet confrontation with V; Valerie’s letter; Lilliman’s death; just to give three examples). The comics’ V is a much less sane character, whereas the movie’s V comes across as more tragically damaged.

Next week, another Alan Moore project he disavowed: Zack Snyder’s take on Watchmen.

Keith R.A. DeCandido is very vigilant in both valued vehemence and vituperation toward vile video versions and valued veneration of valiant video versions of volumes in the vellum ‘verse.